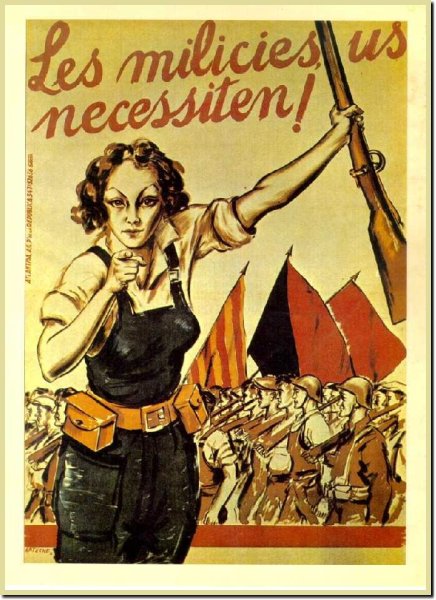

A few months ago I wrote about the 75th anniversary of the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic which was celebrated throughout the state. That weekend I visited a fantastic exposition of Republican and Revolutionary war propaganda posters, in Segorbe.

Today, Spain remembers the beginning of the end.

During the evening of the 17th of July and morning of the 18th, a group of generals of the Spanish regular army raised against the democratically elected left-wing government of the Republic. History says that the murdering of Calvo-Sotelo, a right-wing leader, was what finally provoked the conflict. It was no secret that the same right-wing and some elements in the army had been conspiring for weeks about an uprise. The only question was when, but the government was fooled by general Mola and didn't take really effective measures to prevent it.

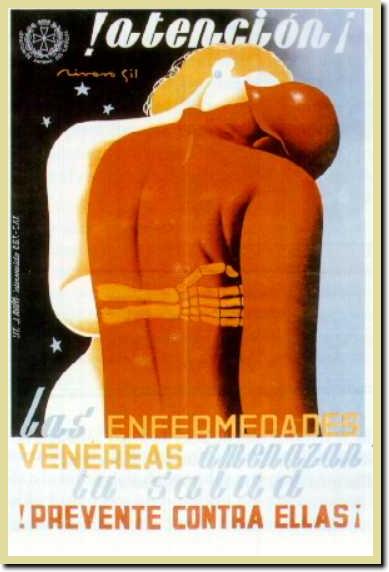

Warning from sanitary authorities against venereal diseases

Mola and Sanjurjo planned to start taking over official buildings and army quarters and quickly seize control of the major cities. During the first hours of their rebelion, they managed to take over most of the southern regions in Andalusia, Extremadura and parts of the Northwest, plus most of the islands and the Moroccan protectorate area. Meanwhile, the Republic did not manage to react quickly due to the weakness of the government, and in the first days of the crisis, the government changed a few times. Finally, the Republican parties decided that to defend the state they should give arms to the unions, and soon after many militia groups were getting organised in the cities, and columns sent off to liberate other towns.

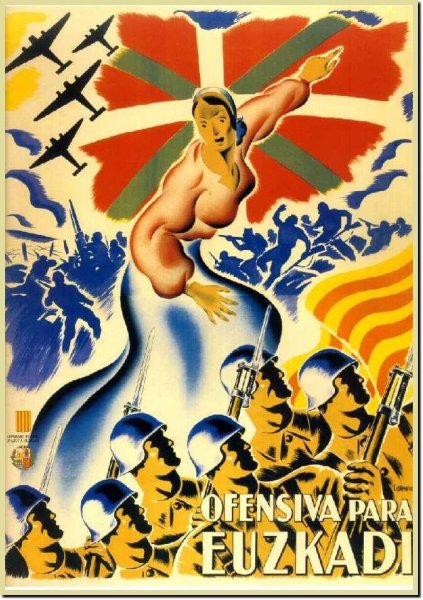

Solidarity of Catalunya to the Basque front

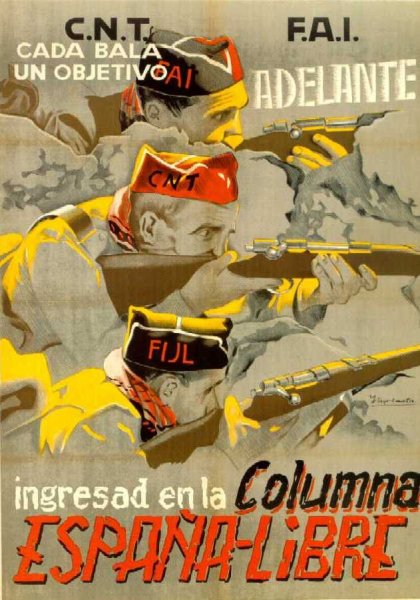

The insurrection was suffocated in Barcelona after some heavy fighting against the military in the Montjuïc castle; the Anarchists of the CNT grew strong in Catalunya and Aragón, and offered good resistance in those fronts.

After the first days of the coupe d'etat, it was clear neither the legitimate government or the rebels calculated how things would go after the first days. The government was confident in being able to end the rebelion as they did four years before; the fascists thought they would have quickly brought down the government with a successful coup. But after the first week, the country was divided in two halves, and both sides of the conflict were keen on fighting, due to the big social fracture during the last months of the government.

The Republic asked for help to the League of Nations, but the United Kingdom and France decided not to intervene, scared about the conflict trespassing the Spanish borders and becoming another bloody war in European fields. The only official external aid came from the USSR and the International Brigades, formed by volunteers of more than 50 nations. Some well-known personalities like Ernest Hemingway or George Orwell came to aid as well. Orwell wrote about his life-changing experience in a Barcelona immerse in the social revolution, where he joined the anti-stalinist socialist party POUM. Badly wounded in the neck, he left the front and went back to Barcelona, and witnessed the assault of the Telefònica by the communists against the anarchists, during the fets de maig, after which the POUM was declared illegal. Orwell captured his experiences in the frontline and Barcelona in his book Homage to Catalonia.

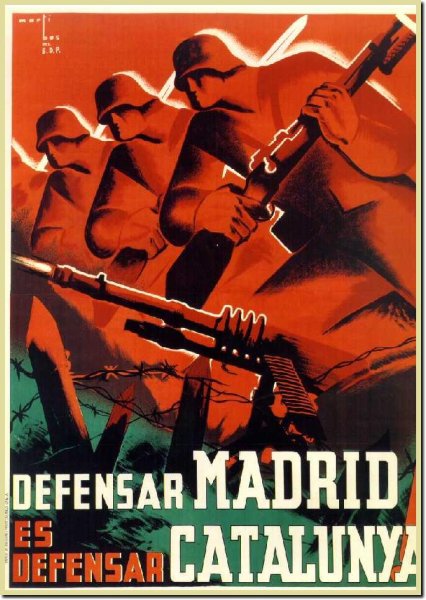

“To defend Madrid is to defend Catalunya”

Franco and Mola, aided by the Northafrican troops and soon after by their fascist allies of Italy and Germany, didn't have big problems seizing the Basque Country and Asturies in the North, but not before making the town of Gernika disappear below the nazi Condor Legion bombing, in what would be a test for the massive aereal bombings of Word War II.

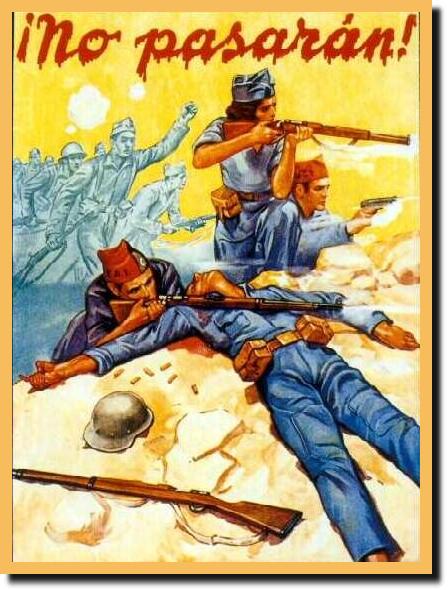

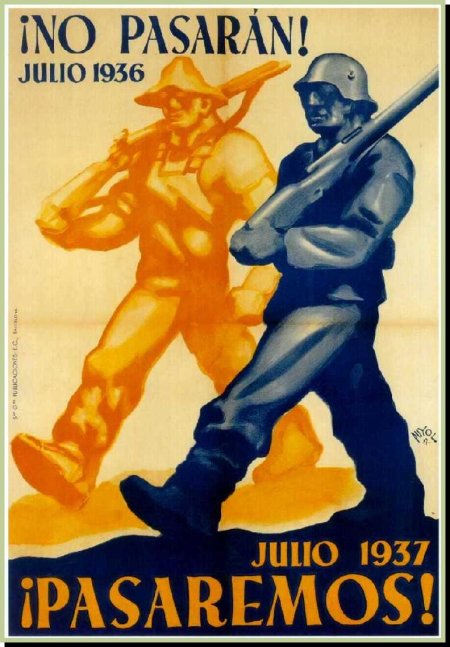

The battle for Madrid was fierce, and the city wasn't occupied until the very last days of the war. The long defence of the capital made was immortalised in the famous phrase No pasarán.

Madrid's “No pasarán”

During the war, anarchist groups controlling fields and towns in Aragón and Catalunya managed to bring a Social Revolution to the area. The people collectivised the land and industries, administered by local assemblies. This experience is regarded as the time when Libertarian Communism has been successful. The experience ended dramatically when the anarchists were treasoned and blocked by the communists, and eventually defeated by Franco at the front.

“Each bullet for a target”

After the first and a half years, the fronts had stabilised in Madrid and the East of Andalusia, until early in 1939, Barcelona fell in Franco's hands, after the bloody Batalla de l'Ebre, being followed by Girona and the rest of Catalunya. The fate of the democratic state was clear. Two months later, Madrid fell and València and the small area still under Republican control surrended.

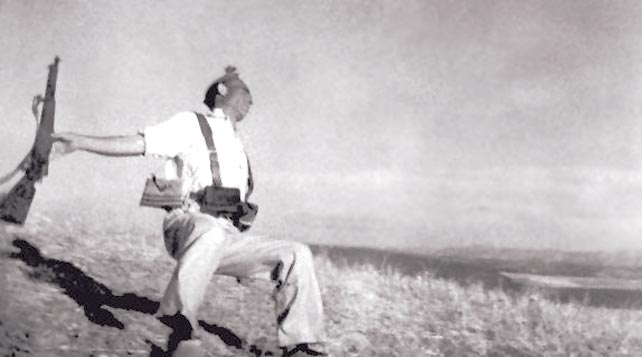

Robert Capa's “Muerte de un miliciano”

Franco declared a totalitarian regime to, according to the fascists, “reconcile” the two Spains. In the first five years of the regime, up to 100.000 were executed in the franquist repression, including the Catalan president, Lluís Companys and many intellectuals. The dictatorship continued executing people until two months before Franco's death, 36 years later. Hundreds of thousands also had to exile in México, France and other destinations, leaving Spain in ashes, road gutters full of scattered bodies and the population facing famine. The cultural elite left the country, making the state's clock go back at least a decade. Their reconciliation really meant humiliation and repression. Many people were also murdered during the war behind republican and rebel lines, but the genocide of the aftermath had was unmatchable.

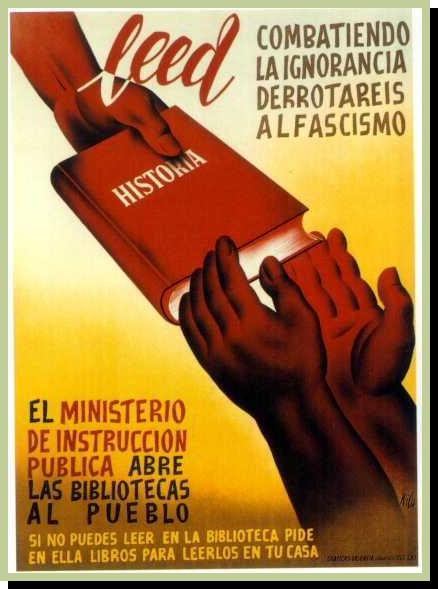

The Republic promoted education among the troups

It is a bit late to restore the dignity of the victims, but not too late. Some associations have been fighting since the end of Franco's regime to get some kind of public recognition for their suffering, for their priceless fight for the legal and democratically elected Republic, for the people who didn't make it.

Excellent anarchist poster rejecting the politisation

of children by any of the three loyal groups

Other people reject these efforts banning them of "revisionism". Not too surprisingly, these are the sons or grandsons of the people who won the war. The current government is about to pass a “Historic Memory” law which aims to give recognition to all these people who gave their lives for an ideal and freedom. Unfortunately, due to pressures from the right, it is probable that the text will be ammended to make it more acceptable by them. I fear it will end up not pleasing the victims at all.

I have a passion for Spanish Civil War related matters, and in the last years I tried to use any opportunity to listen to my Catalan grandmother talk about war affairs in Barcelona, and my grandfather, from a town in the middle of the Republican side of the Teruel front, but born in a very catholic family, about how the war went on in Vall and the nearby mountains.

From the defensive “No pasarán” to the encouraging “¡Pasaremos!”

I know my grandfather only told me the less compromising stories, like how he was sent to dig refuges until he was 16 and apt to fight in the Front, or how he was put in charge of hiding the church's valuable relics in a few barns. He never told me about how life was after the war in the small town. It is dramatic to see that all the people who were old enough to have a sense of what was going on at the time are so old that these unvaluable memories and stories will be mostly gone in ten years.

(Most of the pictures are taken from the Sociedad Benéfica de Historiadores Aficionados y Creadores' website, which has a huge documented catalog)